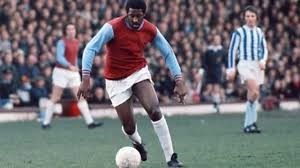

CLYDE BEST: ‘Black’ before all

On his arrival in London at Heathrow airport Clyde Best finds no one to welcome him. Of the West Ham manager in charge of receiving the 17-year-old arriving from Bermuda there is no sign.

“I was completely lost. I waited in vain for someone from West Ham to arrive for almost two hours. At that point the temptation to board the first flight home was really strong. I thought about how much I had insisted against my parents’ advice in order to get this chance. In England, in London, in professional football’.

Ckyde Best studies the tube map.

It reads ‘West Ham Station’.

He decides to head there, convinced that the club that was to welcome him at the airport is located there.

He will not be the first nor the last to make this mistake.

It is a Sunday evening and when he gets off at the bus stop there are not many people around to ask for information.

The young man arriving from Bermuda is probably already regretting not having made the choice he had ‘thought of’ a little earlier and that is to board the first plane that would have taken him back to his sunny and peaceful country.

But Lady Luck decides to lend a hand to the brave and determined 17-year-old.

A passer-by notices Clyde’s discomfort.

He points him to a house nearby.

In that house lives Jean Charles, an English lady who married a black man.

Her sons play in the West Ham youth team.

Ckyde makes his way to that house.

He is welcomed like a son.

That will remain his home until, several years later, he marries Alfreda, the woman of his life and moves with her to a new home.

When he starts playing in the Hammers’ youth team, there is no one who is not impressed by the skill and power of that rugged black kid.

Ron Greenwood, West Ham manager at the time, doesn’t have a doubt in the world.

“Clyde is the strongest teenager I have ever seen on a football pitch.”

In August 1969, when Clyde was only eighteen, he was made his debut in the West Ham ranks.

It was at Upton Park, against Arsenal, in one of many London derbies.

It will end one to one and Clyde will play his part, with great personality.

A few weeks later will come his first goal in the colours of the London ‘Hammers’.

It will be in a League Cup match against Halifax not even ten days after his official debut against the Gunners.

Ron Greenwood believes in him blindly but has no intention of burning the boy.

After a couple of games, he returned to play for the reserves where he ‘made his bones’ (and with his 185 centimetres of muscle he tested his opponents’ stamina) and scored regularly.

He rejoins the team on 27 September 1969.

West Ham go to Old Trafford for a First Division match.

Manchester United plays one of his namesakes, whose first name is George and who a year earlier had dragged the ‘Red Devils’ to the Champions Cup.

“I was impressed. I had never seen anyone do those things with the ball at top speed,” Clyde recalls of that encounter.

“Frankie (Lampard), who was in charge of marking him, even tried hard. There was nothing he could do. He would fall down, get back up without a whimper and then start to drive us crazy again.”

The match ended 5-2 to Manchester United with George Best scoring a brace.

What Greenwood saw in that match, however, convinced him that his big black boy was capable of playing in the First Division and that his partnership with Geoff Hurst (the man of the hat-trick in the final against the Germans that took England to the roof of the world) could become lethal.

In the next match, the one West Ham played at home against Burnley, Clyde Best was confirmed in the starting eleven.

The ‘Hammers’ won by three goals to one and Clyde Best scored a brace.

Everything seems to be going well.

A starting place, goals and the affection of his teammates who welcomed him splendidly and allowed him to fit in with great ease.

Clyde is also a reference point for the many West Indian boys who have arrived with their families in the recent migratory flow. There are also many of them in the ranks of West Ham, not just his two mother Jean’s acquired ‘brothers’, John and Clive.

For all of them Clyde is the absolute idol, more so than Bobby Moore, Geoff Hurst, Martin Peters … the three world champions playing in the Hammers’ ranks at the time.

The problem, however, is another.

Clyde Best is virtually the only black player in the entire First Division.

And he becomes an easy target for the many racists in the stands of English stadiums at the time.

It’s not just the National Front zealots who shout all sorts of insults at him, making monkey noises every time Clyde comes into possession of the ball.

There is a whole host of ‘normal’ fans who are finding it hard to accept that their island is changing and that from the old colonies more and more are looking to England for decent work and a chance to give their families a future.

“I was like a fly in milk!” recalls Clyde Best of that period with his great self-deprecation.

“Impossible not to notice me. There were stadiums where it was really hard to concentrate on the game and pretend nothing was going on.

There are occasions where it’s just impossible.

Like at Goodison Park, where Everton play.

The insults, the choruses of contempt, the monkey cry repeated seamlessly …

“I was really on the edge that day,” Best recalls.

“I got the ball in midfield. I aimed for the opponent’s area with my foot. I had a rage inside that I wanted to smash everything. I jumped over two opponents and the last one, Everton defender Terry Darracott, started to hold me by the jersey and an arm. I dragged him behind me until I got in front of the Everton goalkeeper. I made a feint, he went down and I lobbed the ball into the back of the net. I cheered like I’ve never cheered in my life!” says Best proudly.

An instant later Joe Royle, centre forward and idol of the Everton fans, came up to him.

“Clyde, that’s the best goal I’ve ever seen on this ground.”

The early years at West Ham are for Best the best and most productive.

The attacking pair formed with Hurst works to perfection.

Despite his massive physique, power and aerial prowess, Clyde Best preferred to act as second striker, leaving Hurst the task of ‘target-man’, the main forward reference.

When Hurst was sold to Stoke City in the summer of 1972, Best became the ‘9’, the classic British football forward, the one who almost always plays with his back to goal and has to ‘lift’ the team by ‘deflating’ balls from the defence for his team-mates.

Best struggles in this role and in addition there is another characteristic that will distinguish him for the rest of his career; he only scores ‘nice’ goals. He is not an opportunist, he is not particularly shrewd in the penalty area and there are very few ‘tap-ins’ in his career.

In January 1976, at not even 25 years of age, Clyde Best left the ‘Hammers’ to move to the newly formed US league. His score with the ‘claret & blue’ tells of 58 goals in 221 games.

It would be in the USA that he would play for practically the rest of his career, including in the ‘Indoor’ league that was popular for a few years and where he would win a title with the Tampa Bay Rowdies, also becoming the league’s top scorer.

His only European interlude was with Dutch club Feyenoord in the 1977-1978 season, at the court of Yugoslavian ‘magician’ Vujadin Boskov. It would not be a season for the scrapbook: only three goals in twenty-three matches before returning to the USA in the ranks of the Portland Timbers.

Clyde Best would end his career with the Los Angeles Lazers (also in the ‘Indoor’ league) at only 34 years of age.

“On a few occasions there were even offers from the English league,” says Best, “but for me to play for a club other than West Ham would simply not have been possible …”

ANECDOTES AND TRIVIA

When Clyde Best arrived in London it was only for a ‘trial’, an audition, with the West Ham youth team. In fact, his name was pointed out by one of the Bermuda national football team staff to Ron Greenwood, who agreed to view the boy.

As mentioned, it took only a few days to convince the good English manager (it was he who led the English national team to the 1982 World Cup in Spain) to put Best under contract.

… at this point it is necessary to recall the reason for Best’s abandonment at the airport …

West Ham officials were expecting Clyde Best for the next day, Monday, and so no one turned up for the appointment.

Fortunately for West Ham and for the history of British football Best decided not to take that plane back to Bermuda !

Clyde Best was not the first black footballer to play in English football. Apart from Arthur Wharton, Walter Tull, Lindy Delapenha (who played at Middlesbrough with Brian Clough and became one of his best friends) and Teslim Balogun it was Albert Johanneson who was the most popular ‘coloured’ (as black players were then called) in the English league. Johanneson, who became an absolute idol at Leeds United, was the first black player to play in an FA CUP final, the 1965 final won by Bill Shankly’s Liverpool against Don Revie’s Leeds.

Within a few years after Clyde Best several black footballers arrived on the scene and many of them of great quality. Among the most popular are undoubtedly the three from West Bromwich Albion.

Cyrille Regis, Laurie Cunningham and Brandon Batson were three excellent footballers from that WBA team that was able to place in the very first places of the First Division for a few years.

But it was not West Bromwich who first fielded three black players in their ranks.

It was again Greenwood’s West Ham who, on Easter 1972, fielded Clyde Best and two other promising youngsters from the Hammers’ fertile breeding ground in the derby against Totthenam, the Nigerian Ade Cook and … Clive Charles, one of Mother Jean’s sons!

“It was something incredible,” recalls Best of that day. “I was twenty-one and Ade and Clive were still teenagers. We won the game and Bill Nicholson, the Spurs manager, complimented us and our play.”

As widely recounted, it was not easy for Best to overcome insults and insults. There were stadiums where it was often not limited to a few hundred invaders but took on far greater proportions. Liverpool’s Goodison Park and Leeds’ Elland Road are grounds remembered by Best as particularly hostile to him.

However, there is never an end to the worst. The most significant episode that would indelibly mark Clyde Best’s football career occurred during the 1970-71 season, Best’s second as an immovable starter in the team.

The day before a home game at Upton Park he received a letter with the most explicit content ever: ‘If you have the courage to come out of the tunnel and onto the pitch tomorrow you’ll get a good splash of acid on that dark face’.

Best shows the letter to Greenwood. The police are alerted and deploy a cordon at the entrance to the field. In addition, his teammates, Bobby Moore and Billy Bonds in the lead, circle to protect him.

“I couldn’t not go on the field and give it to those fanatics even though I must admit I was really scared. Fortunately, it all worked out for the best and letters like that never came again,’ Best recalls with relief.

“To this day I still remember the words of my father who always told me that when you take the field you don’t just do it for yourself but for all the people in the club. From the cleaning ladies, to the secretaries, to the field attendant and everyone whose job also depends on how much you and your teammates earn on the field. People who are not lucky enough to earn what you and your mates earn,’ Clyde Best proudly tells us in every interview.

Harry Redknapp, his team-mate at the time, still remembers his first meeting with Best. “We in the first team had just finished training and as we were about to go into the changing room we noticed this black giant training with the youth team. He looked like a 24-year-old in the middle of some kids. They were trying out crosses and his teammates’ shots invariably ended up over the crossbar or several metres out. Then it was his turn. A cross came his way, he stopped the ball with his chest and before it hit the ground, he dumped it under the crossbar. We were all stunned. Behind us was our coach, Ron Greenwood. He came back and went to talk to the youth coach. A few months later Clyde was on our team.

In fairness it must be said that Clyde Best didn’t take long to get into the good graces of more established teammates … thanks in part to his passion for booze, which made him immediately accepted by West Ham’s famous ‘Booze Club’.The evening that effectively ended Jimmy Greaves’ career with the London Hammers has been repeatedly recounted.It happened in January 1971 when West Ham were away to Blackpool for the third round of the FA CUP. When the Hammers’ party arrives in the coastal town a blizzard is raging.The match is likely to be postponed and at this point Jimmy Greaves, Bobby Moore, Brian Dear and our own Clyde Best find nothing better than to embark on a full-bodied drinking ‘session’.They go to bed late and completely drunk.

When they wake up in the morning comes the bitter surprise: there is a pale sun shining down on Blackpool and hundreds of willing supporters of the ‘tangerines’ (so nicknamed because of the orange colour of their shirts) have cleared the pitch, making it accessible. Blackpool ‘passed’ over the ghosts of West Ham by four goals to nil and for Greaves and Dear it was virtually the end with the Club while Moore, a genuine institution at the Club and young Best, got away with a fine and two games in the stands.

Finally the anecdote that a ‘gentle giant’ like Clyde Best remembers most fondly.

“One day a letter came to me. He was an ex-policeman, a West Ham fan, who admitted that he had been one of the most prejudiced and abusive towards me from the stands at Upton Park. He told me that he married a black girl, had children with her to whom he told how stupid he had been as a young man. And then he apologised to me. Closing the letter by saying how idiotic it was to judge a man by the colour of his skin …”