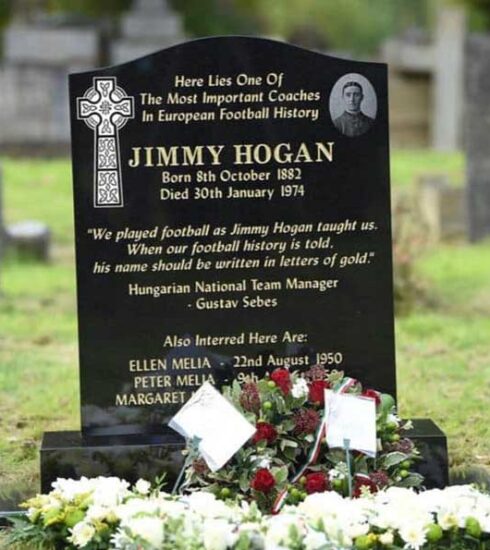

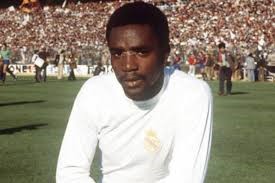

LAURIE CUNNINGHAM: The black arrow

That a Real Madrid player receives an ovation at the Nou Camp in Barcelona is not exactly a common occurrence.

On the contrary.

A few shy applause for some great play by Zidane, Raul, Ronaldo (the phenomenon) Redondo or before that Netzer or Juanito may have escaped … but never an ovation.

It is 10 February 1980.

Real Madrid are playing a La Liga match in the famous blaugrana temple.

It is a peculiar season. The only team capable of challenging the ‘whites’ for the title at the Santiago Bernabeu is Real Sociedad, which is rapidly becoming one of the strongest teams in La Liga. For Barça, however, it is a period of transition. After the era of the Dutch, the foreigners who should now allow the Catalans to make the leap in quality are the Dane Simonsen, and the new signing Roberto Dinamite, a Brazilian centre forward who arrived with great pomp and … who will return to Brazil after a few months as he is unable to adapt to Spanish football and the harsh climate of Catalonia.

The match soon highlighted the difference in depth between the two teams. Pirri and Del Bosque dominate in the middle of the field and Juanito and Santillana are always ready to ‘hurt’ with their skill and experience.

But the difference is being made by a diminutive and very quick striker arrived in the previous summer from West Bromwich Albion, for whom Real Madrid spent close to a million pounds.

His changes of pace, dribbling and technique are making all the difference.

Real Madrid took the lead early in the second half with a goal from midfielder Garcia Hernandez.

A few minutes passed and Laurie Cunningham starred in the play that effectively sealed the match. Having received the ball a few metres inside the opponent’s half of the field, she launched herself at full speed down the wing.

At one point he seems to overstretch the ball, ‘inviting’ the rocky Migueli into a sliding tackle.

Cunningham not only arrived before the defender, touching the ball forward a fraction of a second before Migueli’s hard entrance, but with a truly impressive athletic gesture he also managed to avoid contact with the defender.

When he arrived a few metres from the goal line he slowed down, looked in the middle of the area and then with a delicate outside-right touch put the ball at the feet of the incoming Santillana who sent it into the back of the net.

The rest of the match was a catwalk for Cunningham, who, in the spaces left by Barcelona in search of a goal to reopen the game, was literally at his wits’ end.

More than once during the match there would be heartfelt applause from the stands at the Nou Camp for the play of Real Madrid’s left winger … but it was at the final whistle that the applause turned into a standing ovation with many Barça fans on their feet to pay tribute to this young talent.

In that season Real Madrid (coached by the unforgettable Vujadin Boskov) won La Liga and the King’s Cup, while in the Champions Cup they were only stopped in the semi-finals by Kevin Keegan and Horst Hrubesch’s Hamburg, led by Branko Zebec, Boskov’s friend and compatriot.

Cunningham scores and scores.

And above all, he makes the demanding Bernabeu crowd fall in love with him.

It seemed only the beginning of a sensational career for the young striker born in Archway, a north London suburb, to Jamaican parents.

From the following season, however, serial injuries start to arrive, which significantly reduce the quality of the ‘black pearl’s’ performance.

From Real he began to move on loan to various teams, English, French and Spanish.

When the physical troubles leave him alone he will regain some of his former glory, as in the 1983-1984 season played for Olympique Marseille.

In the 1987-88 season he also made a brief appearance for John Fashanu and Vinnie Jones’ Wimbledon, entering the second half of the famous FA CUP final won by the ‘Dons’ against John Barnes and Peter Beardsley’s Liverpool.

In the following season he would return, for the second time, to play in the ranks of Rayo Vallecano, Madrid’s third team.

It will be Cunningham who will score the historic goal that will allow the small and charming club from Vallecas to return to the top flight.

A contract renewal is ready for him.

Cunningham will be able to return to play in La Liga.

He is only thirty-three years old and if the injuries that have plagued him throughout his career will give him some breathing space, he is convinced he can still have his say in the Spanish top flight.

Fate, however, has decided otherwise.

On the morning of 15 July, just outside Madrid, Laurie Cunningham died in a car accident.

Laurie Cunningham was born in March 1956 in Archway, a district of Islington. From an early age his technique and impressive speed attracted the attention of several clubs in the capital. Arsenal seemed to be his destination, but after a series of auditions, the Gunners’ youth sector managers decided not to offer a contract to the 15-year-old son of a famous Jamaican jockey. The only team willing to include him in its ranks is Leyton Orient, one of the many London clubs that have always sailed in the lower divisions of English football.

Cunningham did not waste the opportunity and soon realised that the boy was ready for the first team.

He made his debut when he was not yet 18 years old.

Soon his name began to circulate among several First Division teams.

But those were difficult times for the very few ‘coloureds’ (as they were called at the time) in English professional football.

Cunningham often had to suffer the intolerance of the fans who populated the ‘terraces’ of English football at the time.

Insults, throwing bananas and peanuts were the order of the day.

So was the cry of the monkey repeated countless times or derogatory terms such as ‘Zulu’ ‘Nigger’ or ‘Coon’.

Sometimes it even happened that some fringe of his own fans were uncomfortable with being represented on the field by ‘niggers’.

But his prowess outweighs even ignorance.

It is John Giles’ West Bromwich Albion, the former great Irish half-back of Don Revie’s Leeds United who manages to beat the competition by securing Cunningham’s services.

Within a couple of seasons, first with Ronnie Allen and then with Ron Atkinson, West Bromwich became one of the most beautiful realities of English football and … also one of the most courageous, as in the WBA starting line-up there were three black players.

Together with Laurie Cunningham there are also the very strong centre forward Cyrille Regis and full-back Brendan Batson.

In the 1978-1979 season West Bromwich finished third in the English First Division, behind two big teams like Liverpool and Nottingham Forest.

“With a couple of signings we would have closed the gap on Liverpool and Forest. Instead, that summer our best players were bought by big teams,’ recalls manager Ron Atkinson.

The first was Laurie Cunningham, whom Vujadin Boskov wanted in his Real Madrid team.

“Objectively … how can you say no to Real Madrid ?” admits Atkinson.

In the summer of 1979, Laurie Cunningham became a player for the ‘merengues’, forming a high quality attack with Juanito and Santillana.

As said, only in the first season Cunningham managed to play at his level before a series of injuries (the first was a fractured big toe on his right foot) ended up affecting the quality of his performances.

ANECDOTES AND CURIOSITIES

Twenty-five years had to pass between Real Madrid and Barcelona before an opposing player was given a standing ovation like the one Laurie Cunningham received.

On 19 November 2005, a sumptuous performance by Brazilian Ronaldinho achieved exactly the same result. This time, however, at the end of Barça’s clear victory at the Bernabeu, with the ‘merengues’ fans on their feet applauding the Brazilian phenomenon.

It was during the Uefa Cup in the 1978-1979 season that Real Madrid’s management marked the name of Laurie Cunningham.

In the round of 16, West Bromwich Albion were up against the Spaniards from Valencia and the two matches were broadcast on Spanish television.

The English clearly got the better of the Spaniards and Cunningham’s performance in these two matches was simply sensational, such that it overshadowed even the star of Mario Kempes, Valencia’s striker and a few months ago world champion with his Argentina team.

Cunningham’s first great passion was dancing. He was a very talented dancer, winner of several competitions held at the time.

He was often ‘pulling’ mornings at these venues. Funky, soul and later reggae were his great passions.

Many believe that this love of nightlife and dancing clubs eventually influenced Arsenal’s decision to disregard his performances.

Upon his arrival at Leyton Orient, it was providential for Cunningham the almost fatherly figure of George Petchey, the club’s manager, who gave the young striker confidence and at the same time the discipline he needed to emerge in the world of professional football.

This is considering that in one of his first away matches with the first team, Cunningham showed up in a pinstripe suit, hat and two-coloured shoes … in pure ‘gangster’ style!

After being discarded by the ‘Gunners’ (‘he’s good, but he has no character’) Cunnigham started playing in the Sunday League, among the semi-professionals. It was at that time that he was pointed out by his coach to his friend George Petchey, manager of Leyton Orient then in the Second Division.

“He’s too good to play at this level. But keep on him, because he’s a headcase!” these were the words with which he was introduced to the Leyton Orient manager.

“On Monday he signed his contract with us. On Tuesday he didn’t turn up for training. I sent someone to his house to call him. He was still in bed sleeping,” this is one of Petchey’s earliest memories.

“When he finally arrived we were halfway through practice. He walked onto the field like it was nothing, with a calmness that bordered on arrogance,” says his teammate Bobby Fischer.

“I remember thinking ‘this guy is either completely crazy or he really has something special as they say’. It took me less than half an hour to realise that the second hypothesis was the right one”.

In March 1977 Cunningham was bought by West Bromwich and just over a month later he would make history in British football, becoming the first black footballer to wear the shirt of an English national team.

He did so with the Under-21s in a match against Scotland, which the English won by one goal to nil.

Goal scored by Laurie Cunningham himself.

During his time at WBA with Regis and Batson it was manager Ron Atkinson who gave them the nickname ‘Three Degrees’, taken from a famous trio of black singers who were raging at the time. Their fame became such that the real ‘Three Degrees’ were guests of West Bromwich Albion and met the three footballers.

In the famous match at the Nou Camp recounted at the beginning, his performance was such that it raised the admiration of several Barcelona players.

The Catalans’ very tough stopper Migueli said “I hope someone took a picture of him as he was running so fast I don’t even know what his face looks like!” while Rafael Zuviria, the man in charge of his marking that night admitted “the only way I can get close to him is when the referee whistles the end because for the whole ninety minutes I never made it once!”.

In the following season came his first serious injury.

The fracture of his big toe against Betis Sevilla that will keep him out for several months.

That season, Real Madrid reached the final of the European Cup in Paris against Liverpool. The decision to throw Cunningham, who had only just resumed training and had played his last game the previous November, into the fray from the start caused a stir.

Real Madrid lost the final to Liverpool by one goal to nil and Laurie Cunningham was a pale stand-in for himself, while becoming one of the main scapegoats of the defeat.

There are many at Real Madrid who have compared Laurie Cunningham’s qualities to those of Cristiano Ronaldo. One of these is none other than Vicente Del Bosque, his teammate at the time and later to become one of the greatest Spanish coaches in history.

“Like Cristiano he could do everything at top speed. His dribbling and accelerations were simply extraordinary. Cunningham’s only limitation, and herein lies the big difference with Ronaldo, was a very quiet character and probably lacking the ambition and willpower needed to really get to the top.”

Although he did not go to excess (he was not known to be a big drinker like many of his compatriots at the time), Cunningham loved the nightlife. Madrid at that particular time at the end of Francoism offered so much and for someone like Cunningham it was virtually impossible to resist the lure of Madrid’s ‘movida’.

It caused quite a stir at the time (and a lot of anger in Madrid’s management) that a few hours after his injury against Betis Cunningham was seen in a Madrid club … with a fresh cast on his foot!

Cunningham’s great legacy remains, more than anything else, that of having been a fundamental example for all black boys of the time. At a time in history when racism in Britain was almost accepted as a form of thought (with a Conservative leader, Peter Griffiths, campaigning a few years earlier with the slogan ‘If you want a nigger as a neighbour then vote Labour’) Cunningham’s courage, determination and ability to let insults of all kinds slide came from the bleachers of most English stadiums of the time.

Cunningham, Regis, Batson, like Viv Anderson at Nottingham or Clyde Best at West Ham before them were the example followed by so many kids who eagerly followed the exploits of their idols.

Ian Wright, Les Ferdinand or Andy Cole are just three of the many who were inspired by Cunningham and co. at the beginning of their (brilliant) careers.